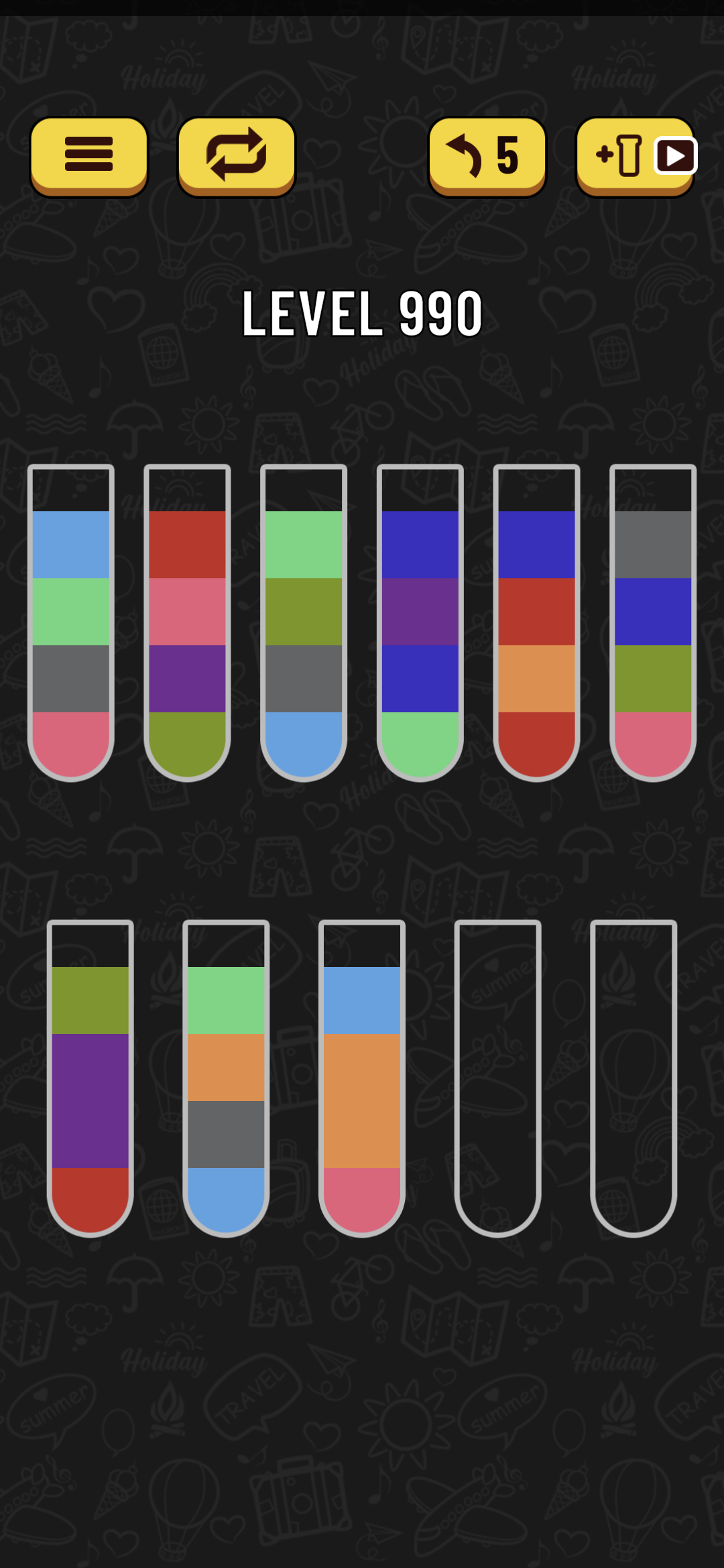

You may have seen ads for the Water Sort puzzle game. In case you haven’t, it’s a pretty standard puzzle game: you’ve got n+2 test tubes filled with n different colors. Your job is to pour from one test tube into another until the colors are all sorted out into their own test tubes. The only rule is you can only pour into a tube that is either empty or that has open space over another section of the same color.

If you know me, you probably know that I consume puzzle games like they’re potato chips. I’ve gone through over a thousand such puzzles, and I’ve noticed that while the standard puzzles are generally quite easy for me, there have been a few that seem to be unsolvable. That is, without voluntarily watching an ad to access an extra empty test tube.

Is it possible that I just flubbed it, that these puzzles are totally solvable and I just didn’t try everything? Of course. But is it possible that this is a calculated business decision on the part of the developers to increase their ad revenue? Also yes.

The Question

At this point, I had to know: am I not as good at solving these puzzles as I thought, or am I being manipulated (yes, despite paying for the ad-free version) into volunteering to play ads just to be able to progress?

The Solution, Part 1: Brute Force Solving

The first part of my solution was to create a Python script that takes the starting state of one of these puzzles and brute-forces a solution. This script methodically tries every possible move, from every possible game state. If it finds a path from the starting state to “solved”, it prints it out step by step.

I plugged in the starting state of several normal, solvable puzzles, and they worked fine. Then I plugged in a seemingly unsolvable puzzle and…it couldn’t find a path to solve the puzzle.

So, there are a few possible explanations at this point. I could have a bug in my script. Or I could have mis-typed the starting state. Or, of course, it could actually be a intentionally un-solvable puzzle.

The Solution, Part 2: Parsing Screenshots

I wasn’t sure if I had faithfully copied the puzzle start state into my script - and, unfortunately, I had already moved on in the game - and there’s no going back! So moving forward, I decided to grab screenshots of the starting states. Now, I just had to figure out how to parse these in Python to repeatedly get the correct starting point.

The Approach

First, I use the Pillow module to read image data. I take the raw image and make a few changes - quantizing the colors to simplify the image, flattening the background to plain black, creating a grayscale copy of the image and running that through an edge detection filter.

I then take the edge-detection data and read through the image, row by row, splitting the image at rows that are completely black. This gives me a couple of scrap images, plus one image of each row of test tubes. I take those two rows of test tubes and “glue” the images together to form one horizontal row. I add a few columns of plain black in between just in case.

Next, I get the edge-detection of the single-row data. This time, I go through the image column by column, splitting at columns that are completely black. This gives me each test tube as its own image. For each test tube, I look at the center column of pixels and create a list of each block of color. This returns something like 1 pixel of light gray for the top edge, a few pixels of black for the headroom at the top of the tube, and then 2-4 chunks of 15-30 pixels each of the colors, followed by another single pixel of light gray for the bottom edge of the tube.

I could just take the relative arrangement of colors and go from that, but for ease of use, I do store the RGB values of each color. This allows me to print out a “fingerprint” of each step in the solution with color coding so that it’s easy to read.

Putting It All Together

With those two chunks of code married, I plugged in a series of 6 screenshots of easily-solvable puzzles. I was delighted to find that my code parsed the images and solved all 6 in under 10 seconds - even on a fairly underpowered Chromebook. Unfortunately, I don’t have a screenshot of the actual puzzle that seemed unsolvable - and naturally, I haven’t stumbled on another “unsolvable” one since starting this project. So for now, I’m just excited that my code seems solid.

Up next, I’ll be working through puzzles in the app, actually hoping to find one I can’t solve on my own. When I get a little more free time, I’ll be packaging my code up in a Jupyter notebook to share with you all.

In the mean time, I hope you enjoy these beautiful results:

| Before | After |

|---|---|

|  |